The Beehive Interview: Wendy Denton, Ken West and a remarkable ‘Cancer Chronicles’

Ken West of Oakhurst lived for 18 months after his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. He and his wife, photographer Wendy Denton, used that time together to collaborate on a remarkable, moving and often light-hearted photo series. (It continues through June at the Chris Sorensen Studio.) In Friday’s 7 section, I talk with Denton about the experience. Here’s an extended version of the interview.

Ken West of Oakhurst lived for 18 months after his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. He and his wife, photographer Wendy Denton, used that time together to collaborate on a remarkable, moving and often light-hearted photo series. (It continues through June at the Chris Sorensen Studio.) In Friday’s 7 section, I talk with Denton about the experience. Here’s an extended version of the interview.

Question: The first photo in your exhibit is of Ken receiving his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Tell us a little about that day. Did the two of you decide that day you would be doing this project together, or did the decision come later?

Answer: Ken had already had a procedure a week or so before that revealed the cancer was showing up as a few spots in his liver. When we went to Dr. Brandy Box-Noriega, the oncologist at Kaiser, we learned what that really meant. Dr. Box-Noriega outlined treatment protocol and discussed Do Not Resuscitate directives, names of chemo drugs, etc. We listened as carefully as we could, but I could see Ken’s eyes glaze over now and then. Later he talked about the random thoughts he had had during Dr. Box-Noriega’s explanation. On the drive home, we talked about how we could best handle this life-altering process. I think it was Ken who suggested we document the entire process.

Give us a little background on Ken as an artist and as a person.

Ken was generous, kind, took in all the animals I brought home, supportive, incredibly bright and insightful. He was outspoken, sometimes combative, especially in the face of injustice. He meditated regularly, had years of post-Vietnam therapy, was funny and wise. Ken had tremendous courage in the face of hard truth.

Ken started taking pictures in the seventh grade and was attracted not only to the art of seeing and capturing moments but to the mechanical gadgetry offered by the camera. He loved taking pictures of wild life, mainly birds, and anything that challenged his skill, patience and equipment. For him, photography was a way of being in meditation with the moment, aware of possibilities and potential.

Tell us about you.

My photographic journey started in Germany in my early 20s. I’ve worked in dozens of darkrooms and explored the nuances of several different kinds of cameras and processes: black and white printing, digital transfers, Polaroid transfers, plastic toy cameras, etc. Often my subject matter falls into the artist-as-advocate category. My series on birds that have been killed by human carelessness in an example. The camera is my therapist, my conduit with the world, a way of connecting while remaining separate. For me, photography is not about an image as much as it is about capturing the connecting point between myself and something in the world that reflects that piece of myself.

Had you and Ken worked together on other photo projects before?

Had you and Ken worked together on other photo projects before?

Yes. We did this in two ways:

(1) We were quite spontaneous in terms of grabbing the dogs and photo equipment and jumping in the car to see what we could find to photograph. Some of the trips were planned, and some were random off-the-beaten-path-on-our-way-to-Fresno kind of thing. Because Ken grew up in Oakhurst, he knew many of the out of the way places. We also went to many near ghost towns in the desert on the way to my dad’s house in Arizona. We photographed whatever came to us.

(2) Ken developed a passion for photographing birds in motion: eating, fighting, flying, playing, etc. Beautiful, dynamic images near home or in the two nature preserves in Los Banos and near Chowchilla. I photographed birds that had been hit by cars. (This is not as creepy as it sounds. The images are really quite beautiful and were featured in an article in the local paper when I exhibited in Paso Robles. Really.) A year or so ago, Ken and I had a show at the Sorensen Gallery that featured our different images of birds.

How often did you make photos for the project? How did you come up with ideas?

Once we locked onto the project, we talked about it all the time. For the entire 18 months, we played with image ideas, experimented with locations, and made many more images than are in the exhibit. We didn’t really have a routine. We got an idea and just did it. The spontaneity was exciting! Probably most of the ideas and conceptual visuals were mine, but Ken made the images come to life. Having been in community theater since childhood, Ken knew how to evoke the feelings we wanted to show. Also, he wasn’t at all shy and would do any image I asked of him.

Coming up with ideas was exciting and fun. I would wake up with fully formed image ideas and sometimes even dream them. Because Ken had a rich background in philosophy, and I studied cultures and religions, we both had rich visual traditions to weave into our images. For example, “St. Sebastian on Chemo” blends the image of an early Christian martyr and the experience of chemo.

In the photo “Have They Staged it Yet,” Ken “performs” on stage at the Golden Chain Theatre. Why?

In the photo “Have They Staged it Yet,” Ken “performs” on stage at the Golden Chain Theatre. Why?

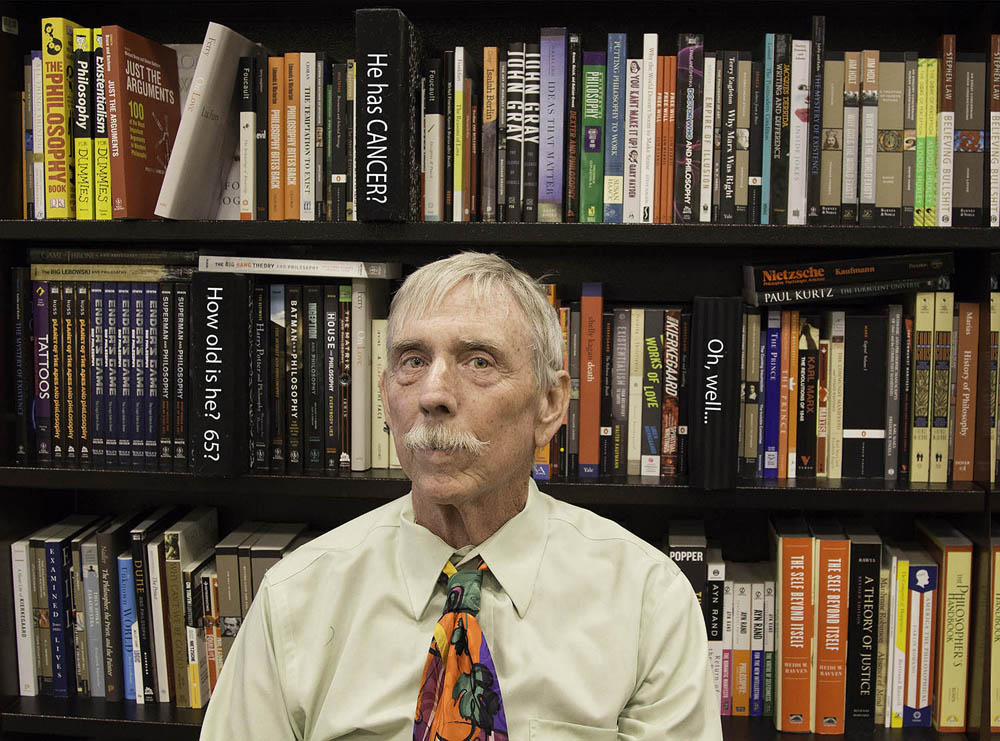

This image is one of three that address the things people say when they don’t know what to say. In “Have they staged it yet?” we are making a visual pun based on the response of a friend when she found out he had cancer. In trying to ask how serious the diagnosis was (Stage 1, 2, etc.) she asked if they had staged it yet. The other two images are “Think of it as a gift” and “He has cancer? How old is he? 65? Oh, well…” (In other words, he’s old and had a good life, so the cancer isn’t really that tragic.)

Taken as a whole, the show has a strong, sassy sense of humor. Does this reflect Ken’s nature, or yours, or both of you?

Oh, this humor belongs to both of us. Ken and I frequently amused each other with our irreverence and disregard for convention. We joked about things that a lot of people wouldn’t even talk about, let alone with irreverence. For example, the last image in the series is of the cremation container that I covered with our photos, sitting in front of the fire extinguisher. If Ken could have seen that, he would still be laughing.

Are viewers surprised by that sense of humor? Have any been offended?

I suppose viewers were surprised in some cases. One friend hated the mannequin image (“The Illusion of Permanence”) because it reminded her of death, which is, of course, the point of all of this. I think people were uncomfortable because we were so open about the fact that Ken was dying, but everyone is dying, they just don’t know when. This project of looking at death gave us an intensely satisfying experience of living, including finding things funny.

I was moved by the photo “Letting Go,” in which Ken pulls an opened suitcase up a paved, woodsy outdoors incline toward a distant but unknown destination as various items (an old camera, a phonograph record, prescription pill bottles) spill out behind. Where did you shoot this? What was the shoot like?

I was moved by the photo “Letting Go,” in which Ken pulls an opened suitcase up a paved, woodsy outdoors incline toward a distant but unknown destination as various items (an old camera, a phonograph record, prescription pill bottles) spill out behind. Where did you shoot this? What was the shoot like?

Driving between Coarsegold and Oakhurst one day, I spotted this road about half way in between. I had already bought the ratty suitcase at a thrift store for another image and put in as many random objects as I could think of. We drove to the site. I positioned Ken part way up the incline and then opened the suitcase so things would fall out. I did place some of the objects in patterns so you could see what they were and placed the flag in the bottom of the image. (Note: Ken served four tours in Vietnam, a source of great trauma in his early life. I considered it important for the dusty flag to tumble out of the suitcase – the first object to be left behind.

What was the most difficult photo in the series to shoot in terms of set-up, technical challenges, etc.?

Probably the most difficult in terms of set up and technical challenges was “Zen Ascension.” First of all, to make sure Ken balanced on top of the table (not shown) and not fall off. Second, to increase my Photoshop skills enough to disappear the table and everything around it (including our curious dogs) and make it look as if Ken really were ascending. All in all, a fun challenge.

Do you have a favorite photo in the bunch?

I love the image of him I made the day before he died. The beautiful planes of his face, the peacefulness in his stillness. He was without fear, and he was without pain.

What did this photo project mean to you and Ken?

This project brought us closer than we had ever been in our relationship. We were completely transparent and intimate with one another. This process facilitated a degree of healing we could not have anticipated. There were no secrets, hidden thoughts, things left unsaid. What I had also not anticipated was the way I released all resentments.

O.K He left the toilet seat up and his clothes on the floor. None of it mattered anymore. In an instant. None of it mattered (and actually never had). Instead, we talked about Janus, the god who could look at the past and the future at the same time and how could we show that in an image. We talked about my self-portrait of my face in a shattered mirror and my initial feeling of being disconnected, displaced. Most of all, this photo series made it impossible to hide or avoid. It encouraged us to look at each other clearly and with honesty.

Once it closes at the Chris Sorensen Studio, are there any future plans for it?

Not yet. I would love for this exhibit to be shown in multiple venues. Ken and I both hoped that others could use our experience and images to promote their own healing and to allow for more conversations about a topic that is not allowed much expression in our culture. Imagine if more people could be open and transparent in the face of such a diagnosis.